Sometime to Return

April 5, 2015

I SPED down Van Alsteen Road, my truck bouncing from the dips in the sun-bleached blacktop. Corn fields, green and thriving, blurred by. My left arm was angled out the window and my hand surfed through the air. I had a cheap, portable CD player plugged in through the cassette slot and speakers with enough wattage to really swallow you, even when the windows were rolled down. Soul Asylum’s Let Your Dim Light Shine was playing on repeat, volume maxed.

This was 1995, summer break. I was entering my third year of college. I didn’t have a girlfriend, hadn’t had one since high school, and I took that as a sure sign something was wrong with me. I spent a lot of time that summer simply driving the empty roads. It somehow gave me the real sense that I was going somewhere with my life, even if I always ended up right back where I’d first started.

Let Your Dim Light Shine had only been out for a few weeks. I was thrilled when I’d discovered it at the record store. I took it as a promise that things would soon be getting better, and I walked right to the cash register without even bothering to look around for anything else. For me, for years, Soul Asylum had been exactly what they’d named themselves—a safe place for my soul.

In the time after I purchased it, I listened to Let Your Dim Light Shine over and over, mile after mile, memorizing it. In my truck-bound solitude, I sang along. Certain lines resonated: Don’t recognize my hometown; We could build a factory and make misery; Please don’t leave me to my own devices. I’d been going to school out west, wintering in the high desert of Arizona, but coming back home to Wisconsin every summer. One of the reasons I’d always loved Soul Asylum was that they also were Midwesterners—Minnesotans. So I drove past acres of corn and potato, past pastures where Holsteins chewed their cud, and I sang. I cut through forestlands where the dappled light created a natural strobe effect, and I sang. Much of the time, I’m sure, I was stoned.

But as I moved down Van Alsteen Road that day, as I slid into neutral and coasted toward the stop sign, I started realizing something new about the music. The day was already weighed down with humidity and now something else was pushing at me: Let Your Dim Light Shine sucked.

Though the revelation had been building for a while, this is the moment when it crashed down on top of me. The change was permanent and whole. Let Your Dim Light Shine suddenly felt scrubbed clean, felt flat, almost cheesy. It was cheesy. As the road-noise faded, the music became unbearable. Had I really just heard a sitar? Today I’d say the record sounds overproduced, but I didn’t know that word back then, and I still don’t have a lot of confidence I actually know what it means now. The music had a kind of perverse sparkle: something digitized, sanitized, wrong. Whatever it was, it was all I could hear.

I sat at the stop sign, the stereo off, my ears ringing. I looked south and then north, wondering which way to go, realizing that it hardly mattered. I felt adrift, something that I’d being feeling for a long time. I felt lost and trapped and claustrophobic, fearful that my disquiet would never end. There was, I believe, a desire to cry. TLC, Boyz II Men, and Celine Dion were all chart-toppers those days. Kurt Cobain had blown his head off. Now my favorite band, the one who’d always been there for me, they’d abandoned me too.

WHERE I grew up in Wisconsin, the MTV show “120 Minutes” ran from midnight to two on Sunday nights. The format was two hours of alternative music videos hosted by some English dude. I wasn’t the kind of kid who could even keep his eyes open past ten, so instead of trying to stay up, I’d program the family VCR and then watch the recording the next day after school.

I wasn’t big into alternative music yet. My dad mostly listened to Chicago and The Moody Blues, and I didn’t have any siblings to guide me in the ways of cool. But my girlfriend had cool sisters in college, and my best friend, Bill, he had cool sisters and cool brothers in college, and they all knew something: they were all listening to Elvis Costello and The Pixies and Camper Van Beethoven, bands from “120 Minutes,” the kind you never heard on any of the local radio stations.

My first encounter with Soul Asylum was on one of those “120 Minutes” tapes, a video for the song “P-9.” The video is in black and white and largely consists of the band—Dave Pirner, Dan Murphy, Karl Mueller, and Grant Young—playing acoustic guitars and singing in a snow-covered farmyard—Grant, the drummer, rapping his sticks on a piece of farm equipment, or a strip of fence. Pigs root about, and there are barns and silos and snowsuited children, hoods pulled up and scrunched around bright smiles. There are scenes of factory workers, and semi-trucks, and industrial areas just like those surrounding the paper mill in Kimberly. The mill was running back then, but today it’s shuttered.

The song is an up-tempo labor tune inspired by a strike at a Hormel Foods plant in Austin, Minnesota. There’d be enough to go around if I could just get around you. In the video, a homeless man crumples to the sidewalk in front of a graffitied wall that reads VOTE FOR A BOSS/ BUSH OR DUKAKIS.

Out of all the videos on that tape, “P-9” was the only one I watched more than once. And I watched it a lot. I’m not exactly sure why it slivered into me, but I think it had something to do with all the things I recognized, the feeling that somehow they were singing about me, about my world, my town. I didn’t have my driver’s license yet, something that I thought made me an expert on the topic of injustice. School was lame. Adults were lame. It was a landscape I knew and felt.

After days of video hypnotism, I had my dad take me to the Exclusive Company, the same music store where I’d later buy Let Your Dim Light Shine. CDs were just beginning to take hold, and no one I knew even had a CD player. My dad was a cassette guy himself, but my girlfriend and Bill and their brothers and sisters were all record people, said that it was a better sound. At the store, there were only a few Soul Asylum albums to choose from, so I picked the EP Clam Dip and Other Delights, which included “P-9.”

My father, who’d been hanging back, came over to see what he was about to pay for. The cover of Clam Dip plays off Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass’s Whipped Cream and Other Delights. Instead of Alpert’s coy, brunette female covered in whipped dairy and holding a single red rose, Clam Dip’s cover features a pale Karl Mueller, Soul Asylum’s bassist, slathered in mounds of dip. Clams dot the white mess. There’s even a half-smothered salmon.

My father didn’t say anything when I showed him the record. Instead, he gave me a look I’d see often over the coming years—a look that sometimes came off as disapproval, but was really just a kind of simple bewilderment.

“You don’t want to get it on tape instead?” he asked. It was like his whateverth time asking me.

At home, I slid the record from the sleeve. Side B first, carefully dropping the needle, straight to “P-9.”

IT’S easy to chart Soul Asylum’s sound by the labels they were signed to—Twin/Tone, A&M, Columbia, and Sony—and in my mind it goes great, to greatest, and then starts sliding downward.

Clam Dip was the last album Soul Asylum recorded with the now-defunct Minneapolis record label Twin/Tone. The Replacements, Robyn Hitchcock, Ween, and The Jayhawks: they’d all been Twin/Tone bands. Clam Dip was supposed to have preceded Soul Asylum’s first major-label release with A&M Records, who they’d signed to as part of a distribution deal with Twin/Tone, but the A&M release had been delayed. The spoofy cover, important since Herb Alpert is the A in A&M, hadn’t gone over so well.

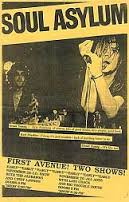

By the time Soul Asylum signed to A&M, they’d already been together for seven years and had released six albums. Their first incarnation was in 1981 as Loud Fast Rules, a three-piece with Dan on guitar, Karl on bass, and Dave on drums. They played their way through house shows and local clubs and eventually made it to First Avenue, that vaunted Minneapolis venue. Dave moved to rhythm guitar and vocals, and the band added Pat Morley on drums. In 1984, they changed their name to Soul Asylum and signed with Twin/Tone. Grant replaced Pat, cementing the line-up for the next decade.

The Twin/Tone albums are loud and rough and fast, full of the punk ethos, but for a few moments they’re also folksy and bluesy and country-ish, reminiscent of the stuff you’d hear at any sleepy, mirror-balled tavern in the Northwoods. Fellow Minnesotan Bob Mould produced the band’s first two albums—Say What You Will, Clarence… Karl Sold the Truck (a rerelease), and Made To Be Broken—and for the most part it’d be Bob’s band, Husker DÃœ, along with The Replacements, especially the Replacements, that’d be hailed as the great alternative bands to come out of Minneapolis. Ten months after they’d released Made To Be Broken, Soul Asylum issued While You Were Out, an album whose guitar-heavy opening track “Freaks” became anthem-like for me, a geeky teen struggling against the restraint of jock culture, while at the same time trying to participate in it. Just another freak/ Be another freak. The band toured heavily for the next two years, eventually gaining enough success to quit their day jobs, which only allowed them to be on the road more

On the back of Clam Dip it reads: “Their cruddy appearance and irascibility brought an immediate response from the industry. ‘Not with a 2000 foot pole,’… The leeches, bloodsuckers and weasels refused to have lunch, and the phone never rang. Life goes on.”

I TOOK every art class offered at my small high school, a total of four. Mr. Gehl, a patient and distant teacher, taught every single one. Once during the sculpture unit he told me to let my father know he got an A on the metal kite I’d turned in, which was fair enough, since my dad had done most of the work.

The mix of students in each class was similar, and the kids crossed all grade levels: there were band geeks and drama geeks, druggies, metal-heads, some other kids who’d migrated over from shop class, and then some kids like me, kids who mostly followed the rules and had vague ideas about become architects or accountants.

One period I asked Dana Milbank—band geek—if she’d ever heard of Soul Asylum. Dana almost always dressed in black, and she had a haircut where the back was shaved and the front was long and tapered and hung over her eyes. Sometimes she’d dye her bangs green or red or orange. She played sax in the marching band. She was creative in everything she did. People called her a Satan worshipper.

Dana lent me her cassette of Hang Time, Soul Asylum’s first A&M release. In one review, Rolling Stone called it, “… one of the most eloquent guitar-band albums since Neil Young’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.” I do not have to go on about how incredible an album Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere is. Everyone knows this. Hardly anyone knows Hang Time.

I ran track that year, the 400 and the 4 X 400 relay. I listened to Hang Time before meets, trying to quell my nausea, rewinding certain songs and sitting through the screech of the tape spinning backwards so that I could hear the chorus again. But I didn’t just listen to it there, I listened to it everywhere—in my room, in the backseat of my parent’s minivan, while walking home from school and watching Elisabeth Opsahl, the Norwegian exchange student, pass by on the bus and not notice me at all. I projected so much onto those songs, and there’s no way to catalog it all—the shyness and awkwardness, the Lutheran guilt, the desire for a cosmic fast forward button so I could just get high school over with and move somewhere new, which assuredly would be better. I didn’t just memorize those songs, I stitched them to my heart.

I continued recording “120 Minutes” faithfully each week. Eventually I captured videos for “Cartoon” and “Sometime To Return,” two of my favorite songs from Hang Time. When my mom and dad would leave me home alone, I’d go downstairs to the living room and strike up the VCR and turn up the TV until the sounded warped. I’d make those videos real, pretend I was there in the crowd during the live shots. Except for the State Fair when I was six, I’d never really been to a concert. I watched and memorized and mimicked. With the house empty, I’d jump around and sing and thrash an air guitar until I was panting and sweating, purging my teenage pent-up-ed-ness, screaming at the peak—Never Forever Whatever!

One time, out of exuberance, I punched a hole in my bedroom door. When my dad came home and asked what the hell had happened, I told him something way closer to the truth than he thought.

“I have no idea,” I said.

A HANDFUL of people were waiting in line, and I fell in behind them. The flyer said the doors opened at 7:00, but I went an hour early, thinking that I wouldn’t even be able to get a ticket. How could they not already be sold out?

The people in line all looked like Dana and her band geek friends—they wore Mohawks and leather jackets and had cigarettes tucked behind their ears. I think I had on a pair of cargo shorts. We’d lined up in a wide alcove in front of the ticket window, the walls covered with posters for upcoming shows. When my feet got tired I sat on the ratty carpeting. Flattened cigarette butts poked from underneath the baseboard. My girlfriend and I had split up and gotten back together and split up again. I wanted a buddy to be there, maybe Bill, but I knew that Bill didn’t like Soul Asylum, and that he could be totally pissy sometimes, though not as bad as I could be. I didn’t say a word to anyone the whole time, just tried listening to all the conversations at once and to not get caught staring.

About four hours later, after two loud opening bands and the heave and thrust of their accompanying mosh pits, Soul Asylum was up. The same guitars I’d seen in those videos—Dave’s unpainted Fender, Dan’s gold Gibson—were right there in front of me. The lights went down, and the weight of the crowd settled into my back. I pushed against it. I had still not talked to anyone. My clothes were soaked through with sweat, and the air was as ripe as a locker room after gym glass.

I don’t remember the first song they played, just that it was loud, really loud, and that almost all of us in the small crowd simply stood there, our hands stuffed deep in our pockets. We tapped our feet and bobbed our heads oh so slightly. As the song finished, a few people clapped and whistled, but it sounded muffled to my deafened ears.

The band took time to tune their instruments, strumming a note after each adjustment. Dave stepped to the microphone and looked at us sheepishly. He wore what he always wore: torn jeans, a thin t-shirt, ratty Chuck Taylors. His long blonde hair had started to dread. When the back of my hair had finally gotten long, my parents told me that I had a choice: I could get it cut, or get it permed. So I got it permed, finally chopped it off a few weeks later.

Dave said, “Let’s try this.”

At the first note of “Little Too Clean” the crowd, each of us, all at once, began jumping and dancing and banging our heads, waving our arms in the air, curling our fingers into devil horns. Up on the stage, his hair a wild mess, Dave rocked back and forth, pressing his hips into the back of his guitar. Next to him, Dan leaned toward a microphone, keeping time by metronoming his foot forward and back, kicking it into the ground on the down swing. In the center of the room, in the pit, people circled one another, pushing and shoving. And because I was a teenage boy, and because what all the other teen-age boys were always talking about was how important it was to not be a pussy, I pushed and shoved and tried to hold my own.

The songs piled on without a break that night. At the time, though I didn’t know this, Soul Asylum had already earned a reputation as one of the best live bands in America. They remain the best live act I’ve ever seen. This has to do in part, I know, with the timing of everything, with the fact that Soul Asylum and I converged at these particular points in our lives. Today when I go see a band, and I see more bands these years, I most often sit in the back and sip a beer. But back then I was full of something else, some innocent energy that has since faded. My brain was undeveloped and smooth, something that probably hasn’t changed as much as I like to think it has. When a crowd surfer started to fall through I’d make sure to push them back up, even if I got kicked in the face—or just so I might get kicked.

Soul Asylum’s acclaim as a live band partially had to do with the covers they did. The night of my first concert they performed several. I’d heard “Sexual Healing” before, but I had no real idea who Marvin Gaye was. They also covered Foreigner’s “Jukebox Hero,” and even the “The Hokey-Pokey.” Google “Soul Asylum” and “Minnesota Music Awards” and you’ll find one of the most brazen versions of Wild Cherry’s “Play That Funky Music” on film. I’d heard all these songs before, but Soul Asylum turned them into something else entirely, a kind of sonic testimonial about roots and reinvention.

Sometimes Dave and Dan quibbled with one another on stage and seemed to forget about the audience. They liked feedback and distortion, and they often ended their shows with their backs turned to the crowd, milking an endless and abrasive buzz from the speakers, which is what they did that night. They propped their guitars, still blaring and wailing like sirens, against the amps, and then they all walked off, raising their bottles of Rolling Rock to us. Other times Dave would ask if anyone in the crowd knew how to “play this fucking thing,” and he’d hold out his guitar and invite folks up on stage to join the band, letting the show devolve into a wild jam session.

But that’s not Soul Asylum anymore. Nor is that who I am. Perhaps those Soul Asylum shows I attended remain so precious, so unmatchable, because they can’t be repeated. No matter how often the songs seem to lead me most of the way there whenever I hear them, I can never return to that time. It seems like it should be way easier to say that that’s okay.

After the concert that night, unable to sleep, a high-pitched whining in my ears, I stared at my bedroom ceiling and tried not to move my head, my neck in such pain that I wondered if maybe I’d actually broken it from moshing so hard. How cool would that be? Cooler, I was sure, than anyone could even know.

AND the Horse They Rode In On came out my junior year. This should have been Soul Asylum’s big breakthrough record, but A&M did little to promote or support the album, and the band floundered. The alternative music crowd that had buoyed them for so long complained that the album wasn’t hard enough or real enough, that it didn’t—as has been said of almost every Soul Asylum album ever—have the same energy as their live shows. The mainstream crowd, well, they still hadn’t even heard of Soul Asylum. I thought it was the band’s best album yet, and still might be my favorite.

There is no doubt that the songs on And the Horse depart from past albums, though how much a departure is debatable. The music as a whole seems less restrained, but also less rough-hewn. The loud-fast-rough is still there, but there’s a more sophisticated flirtation with country and soul and even the power ballad.

By my junior year I’d quit track, had pretty much quit all team sports, except for soccer, and I’d started to get into cycling. In the coming months I’d have to start applying to colleges, because it was definitely expected that I attend college. Douglas Coupland would publish Generation X. Dahmer would get caught. Operation Desert Storm would begin and end, the oil wells still burning. After school, or on the weekends, I’d go for long bike rides, following the grid of roads that connected all the dairy farms, and I’d try to disappear. Every twenty miles or so there’d be an old settler’s cemetery, often unkempt, with maybe ten or twelve headstones and a big shade tree. Sometimes I stopped to look around. Mostly, I kept going, lulled by momentum.

The first single of And the Horse was “Easy Street,” a song hard on the snare and filled with lyrics about perseverance, a sentiment that resonated with me: I, bored teenager. The video for the song was filmed in Wisconsin Dells, a lit-up tourist town along the Wisconsin River. Part of the video showed circus clowns and trapeze artists. Another part showed the band at a Make Your Own Rock and Roll Video shop that happened to be owned by my ex-girlfriend’s uncle, the kind of place with a green screen and costumes and a wide catalog of songs for you to lip sync. I felt stunned and betrayed that my ex-girlfriend hadn’t let me know Soul Asylum was recording a video in the Dells. She said her uncle hadn’t even known they were a real band, and that they had horrible body odor. I’m sure I ran for my bike after she told me.

There’s a story-telling quality to “Easy Street,” a quality that almost all the songs of And the Horse share. It’s there on earlier albums, too, but I didn’t notice it the same physical way. I’d peddle out of suburbia with songs in my skull, the long flat horizon ahead, blue silos breaking up the space. And in that space, in all that distance I had to traverse, I began to fall in love with stories. Slowly, as my legs filled with lactic acid, as Dave’s voice help shoulder the miles, I began writing my own stuff, began playing with words as I moved. I’d compose stories for the people in the cemeteries and stories for the million different ways my life was going to go, a story for each ear of corn I passed. I thought of poems, all of which were shitty, that were capable of stopping a school bus.

After the lackluster response to And the Horse, Soul Asylum went back to their day jobs. Due to their mega-loud shows, Dave had developed tinnitus, a painful hearing problem that would only get worse if the band kept playing the way they did. They considered shutting things down and breaking up.

ONE of the schools I’d applied to was the University of Montana. I was one of like four kids in my class to even be thinking of school outside of Wisconsin, something that made me feel more badass than it should’ve, so one period during health class I leaned across the aisle and asked Nikki Hofkens to Winter Spree.

Once Nikki said yes, I pretty much stopped talking to her. The next couple of classes were agonizing. We’d get in our seats, I’d look over at her and not return her smile, and then I’d turn to the front of the room, or bend to the paper on my desk, the little me-voice inside my head commenting on how badly I was blowing it.

Spree itself went better. I got to dance with Nikki Hofkens, got to run my hands along her hips, got to take in the sweet smell of her hair-sprayed bangs. During one song she clasped her hands around the back of my neck and I nearly shivered. We didn’t share the same group of friends—she was a cheerleader—and as we slow danced, as we slow turned, Nikki looked around the room and commented on her peoples, waving to her girlfriends, shrugging her shoulders when they mouthed, “Are you having fun?”

After the dance, Nikki took me to Eric Bruch’s. Eric was one of the most popular kids in school, one of the rowdiest, one of the most in-trouble. His mom and sister were gone somewhere that night. Outside, it had begun to snow. There was a street lamp right in front of Eric’s house, and the flakes cut across the light. A group of people were sitting at the kitchen table and playing spoons. Some guy—I think it was Kevin Weyenberg—came and sat on the couch with me, and we nodded to one another. I had a warm can of beer in my hand. I hated the taste.

I’d been watching MTV. A set of commercials finished. There was a VJ and an introduction, and then Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” came on.

My memory says that this night, this particular airing, was the video’s premiere, though I don’t think that’s factually true. What must be true is that this is the first time I saw the video, that it was the first time I’d heard Nirvana.

Tattooed cheerleaders, a mosh pit in the assembly hall—it was like some stand-in, mullet-free version of my high school. I leaned forward, elbows on my knees, and the images took hold of me like few others had. I am telling all this because here is a moment where my foundation begins to crack apart again. Here is the beginning of a cultural shift, a shift that would eventually allow Soul Asylum some stardom.

Of course, part of those seismic feelings in me had to do with Nikki being in the kitchen and drinking shots with her old boyfriend, and with the fact that I’d ditched all my other friends to hang out with her. I was trying so hard to craft an identity back then, and Nirvana felt like a new kind of divining rod. Even though I didn’t really know who I was, I knew that night that I wasn’t like the kids at Eric’s. Now I think that none of us are so much different from each other, that we are all just looking for a little love.

When “Smells Like Teen Spirit” ended, the kid on the couch looked over at me. I’d made up a million stories about Nikki and I, most of which ended with us making out somehow, but in none of them had I imagined that song.

“That was totally awesome,” I said, nearly panting.

“Kind of,” he went, “I guess.”

MISSOULA, Montana. A month of college had passed. My roommate didn’t like Grave Dancer’s Union at all. I didn’t much like my roommate, but I don’t know if I ever told him directly. I said I’d start using my headphones more.

How did I feel about Grave Dancer’s Union? At first, I loved it. The music seemed like a natural, grungy step from And the Horse, and many of the songs immediately connected with me. School so far had felt friendless and disorienting, and the song “Homesick” became an analgesic. “Somebody to Shove” described a constant feeling I had, one I could never act upon.

The release of Grave Dancer’s Union put Soul Asylum back on MTV, and most of the interviews and new clips of the time—ah, Kurt Loder and Tabitha Soren!—focused on whether or not Grave Dancer’s would be the one for the little band that almost could. Would this be the one, the album to take Soul Asylum out of the alternative underground and into the mainstream?

The band looks uneasy answering the questions. Nirvana’s Nevermind had broken through and gone gold, altering the machine. Alternative and grunge were the new thing, and if it was new you had to get on it. Here was Soul Asylum, something to get on. The band had taken its share of bruises, had been struggling for ten years, and they were skeptical. But they were also on a new label, and it looked like Clinton was going to be President, it looked like everything was going to be different.

Their third release was the one that did it. “Runaway Train,” a song propelled largely by its video, eventually reached number five on the Billboard charts and won the band a Grammy for best rock song. The video, whose opening shot reads THERE ARE OVER ONE MILLION YOUTH LOST ON THE STREETS OF AMERICA, features photo after photo of actual missing children—their names, and a Lost Since ______ written below their faces.

It’s a good song, though for me it’s been killed by repetition. And it’s hard not to attach the images for the video onto the lyrics, hard not to attach the idea of runaway teens to the song now, though that wasn’t always the case. As I began to feel more out of place in Missoula, as I began to feel a kind of heartache I’d never felt before, one almost panicky about how many miles separated me and my family and my old friends, lyrics like I can go where no one else can go/I know what no one else knows spoke directly to my isolation, however self-imposed it was.

As “Runaway Train” took off, the song was all over the radio, even in Kimberly. It was good to see Soul Asylum getting their dues, but something about their growing popularity felt uncomfortable. Soccer moms were now rocking out to Soul Asylum. The band played Leno, Letterman, made the cover of Rolling Stone. Dave would even dump his girlfriend and start dating Winona Ryder, which some fans called a total sell-out move, and which probably was, but it didn’t matter to me because I was in love with her too.

Clinton became President, and everything did kind of seem like it was going to be different until it wasn’t. For the signing of Clinton’s National Service Act, Soul Asylum played a gig at the White House. Clinton had already been called the rock and roll President, so why not? In an MTV News report from the event, Tabitha Soren asks a dark-haired and unspectacled Wolf Blitzer if he’s ever heard of Soul Asylum before. Five months earlier he’d been reporting about Waco.

“No,” he says, chuckling. “I can honestly say I’d never heard of Soul Asylum before today.”

Tabitha calls the attendees bemused. Soul Asylum is playing a cover of “Don’t Stop.” All the guests are sitting down. There’s a shot of an old generic white guy in a suit, his fingers jammed in his ears.

TWO years later, I’d have my moment on Van Alsteen Road. Afterwards, I’d stop listening to Soul Asylum altogether. In an attempt to get rid of a lot more than some CDs, I’d purge their stuff from my collection, all but And the Horse and Hang Time. Grant Young would split from the band. I’d take a brief journey into hip-hop. Still more adrift than planned, I’d graduate, get a dog, and then get engaged.

Not long afterwards, Soul Asylum released Candy From A Stranger. The album enjoyed moderate success, but nothing like Grave Dancer’s Union. I didn’t buy it, didn’t even go and look for it. If one of their songs came on the radio, which was getting less frequent, I’d turn the dial.

I returned to Wisconsin and got married. There were muggy summers and long dark winters, and my wife and I cycled through them repeatedly, growing distant from one another all the while. I never admitted to anyone about ever liking Soul Asylum, and would sometimes disparage them and actually pretend that I never did like them—pretend that I never actually thought they were the greatest band alive.

A few days before our cross-country move to Oregon, I cheated on my wife. Though it was an act of an entirely different scale, I think it came from the same impulsive and superficial place as did my decision to purge all my old CDs, a place of flailing arms and desperate leaping, gestures meant to hit some universal reset button, a button that even then I knew didn’t exist. The drive west was lots of yelling punctuated by bouts of silence. Every once in a while we acted like nothing was wrong: stopped at Wall Drug and shared an ice cream cone, pointed out new birds on the side of the road to one another.

Three years after making it to Eugene, after buying a house we couldn’t really afford, after my dog got cancer and had to be put down, we finally got divorced. We sold the house, and my ex-wife drove off with her new man, and I ran away to Costa Rica, hoping to find my life again. I came back with two new front teeth from a kayaking accident and a fresh scar on my forehead from my going-away party. Instead of returning to my job, I left most of my things in storage, packed the rest in the back of my pickup truck, and headed more-or-less for Asheville, North Carolina, where some old friends had moved.

My friends put me in their guesthouse, an old barn they’d partially renovated. I spent the days sitting by the creek at the edge of their property having a minor breakdown. Some days I’d go kayaking and push myself down harder and harder rivers. Other times I’d drive into Asheville and walk around and try hard to picture myself living there, but the old anxiousness that couldn’t be cured by kayaking would come back, and I’d head right back to the creek so I could sit there and hide. Nearly six weeks later, most of my money spent, my friends completely annoyed, another bill on my storage unit coming due, I pulled myself back together enough to head back to Eugene, which means pulled not very together at all.

I put in ten and twelve-hour days behind the wheel and then slept in the back of my truck. I paid for gas with a credit card, right there at the pump, and my only human interactions were if I went inside to buy some coffee or a Mt. Dew, or when I was paying at a drive-thru.

Cutting through Wyoming one night, the land empty and silent, I was struck with a sense of fear and loneliness more severe than any I’d ever felt. My heart knocked in my chest, and my breath grew rapid. With so many miles already driven, with so many more to go, I started to believe that I wouldn’t make it, that I didn’t have it in me to survive, that all the cracks had finally been too much. Everything I’d been running from, which I guess was really just myself, now seemed inescapable. All the mistakes I’d made, all the hurt I’d inflicted and experienced, all the wasted opportunities, all the close calls—they filled up the cab of my truck like water, and I felt as if I was drowning.

I scanned the radio, one end of the dial to the other. I didn’t want music. I needed to hear a human voice, gentle sounds, a companion. I wanted someone to talk to me, to say something, something to sooth the unrelenting ache of the road. It didn’t matter what, just words.

Finally, I found the signal from a NPR station. It happened to be pledge week, and the announcers were talking about how far they were from reaching their goal, how important that money was. The reception faded in and out. In the background, phones began ringing.

The regular broadcasting that night came only in snippets. The announcers kept cutting away to return to the pledge drive, where the totals kept rising. Outside, the stars stretched across the sky. Way up ahead, two red dots, the only other car I could see, hovered in the blackness. As the station got closer and closer to its goal, I started feeling something like hope. Not avoidance, but hope. When a matching donation put the funds over the top, I almost started crying.

Not too many miles later, when the reception crapped out completely, I flipped past all my usual CDs. I’d grown so sick of them all, so sick of music in general. Way back into the collection, there they were. Why had it been so long?

I started with Hang Time, kept creeping the volume up louder. It’d been a decade since I’d listened to them, yet the lyrics came back instantly, effortlessly. The guitar riffs, the rhythms, the memories—they all returned. I knew them all by heart.

As “Cartoon” played, which might just be Soul Asylum’s best song, that’s when I really broke open, that’s when I really started balling. I cried and sang, and all those things I’d projected onto those songs so many years ago were still there. I was still trying to work my way through them. I still am, still will be.

I sang my way through the rest of the songs on Hang Time, sang my way through And the Horse twice, sang my throat raw. I started to feel like everything was going be okay then, that I’d survive the rest of the drive home, that I’d make it to Oregon, find a job, and come out from under my bills. I’d fall in love, get married again, and help raise a daughter.

That night I thought back to a time on the bus in high school, the team on its way to a track meet. I was listening to Dana’s copy of Hang Time. I used to get so scared before meets because I knew the running was going to hurt. The faster I made myself go, the more it was going to hurt, which you weren’t allowed to use as an excuse. As the bus lurched along, and Wisconsin streaked past, I remembered thinking that Soul Asylum was the kind of band I would be—that if I could make music, it would be this music, this music was me.

The running was going to hurt, but certain things could help you face it. I’ve repurchased all the Twin/Tone releases, have the entire discography up through And the Horse. In 2005, following a long struggle with throat cancer, Karl Mueller passed away. Shortly thereafter the band released The Silver Lining, which Karl had helped record. It’s another album that’s not for me. Dave and Dan still play*, are still recording, and that means something, maybe even everything. It goes on and on, and it won’t go away.

*In 2012, Dan Murphy left Soul Asylum, which probably deserves its own essay. Dave Pirner continues to lead the band.